On Camera

Published:

Have you wondered how cameras turn an object in 3D space to a 2D image? This post covers the entire process and goes very deep into half of that process. I am writing this post because this is such a simple subject and yet there has not been any post that clearly explains it (mainly due to too-many terminologies with the same meaning, and most posts just analyze math without even telling the basic concepts). I personally struggled a lot on this during my own research, so I hope this post will help whoever sees it in the future.

Space

Before diving into cameras, we need to first understand space. Space is probably the most basic and important concept to understand. Unfortunately, as far as I know, no tutorial on cameras ever covered space. I don’t have a precise definition of space but you can essentially understand space in this way: In object X’s space, X itself is at (0, 0, 0). No matter X’s rotation, The lines that cross X’s centroid orthogonally from “left-right”, “high-low”, “forward-backward” are x-axis, y-axis, z-axis, respectively. This definition means that coordinate axes in different objects’ spaces might be different. The meaning/significance/essence of an object’s space is that it captures the relative transform of other objects. To better illustrate this, consider the following example:

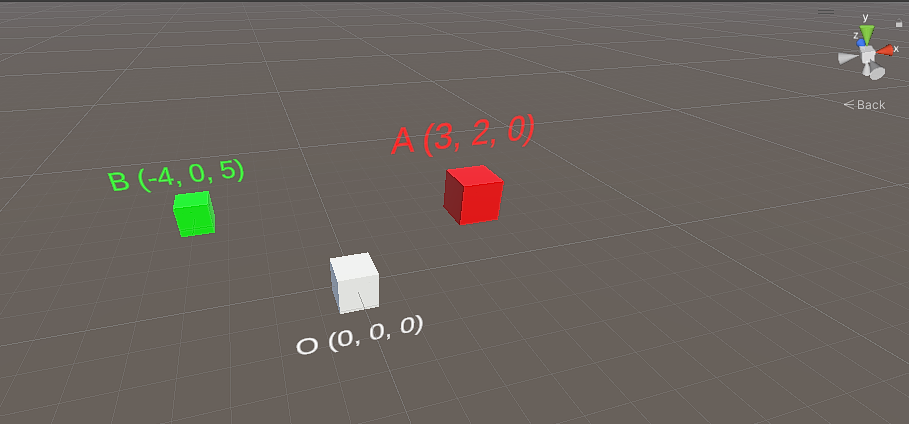

In this picture, the coordinates of Cube O, Cube A, and Cube B are (0, 0, 0), (3, 2, 0), and (-4, 0, 5) in world space (or, Cube O’s space since it’s at origin). They mean that starting from origin or Cube O, we should go +3 units in x-axis, +2 units in y-axis to reach Cube A, and we should go -4 units in x-axis, +5 units in z-axis to reach Cube B. Now, if we take everything in Cube A’s space, Cube A itself is at (0, 0, 0), and Cube O is located at (-3, -2, 0) because we need to go -3 units in x-axis, -2 units in y-axis to reach Cube O. Similarly, the coordinate of Cube B in Cube A’s space is (-7, -2, 5).

Extremely simple concept isn’t it? just to reiterate, an object’s space captures the relative transform of other objects.

“Space Transformation Matrix”

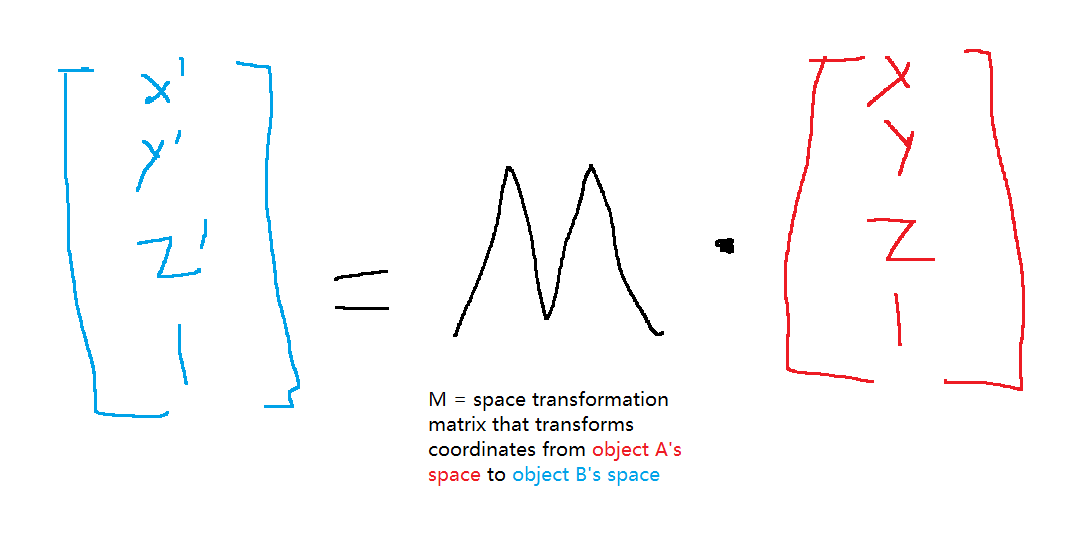

In the above content, we learned what is space and saw an example of turning the coordinate in one space to the coordinate in another space. However, the reason why we can easily derive the coordinate/space transformation is because all cubes are not rotated. If we take into account of rotation and scale, we need a more systematic way of doing space transformation: “space transformation matrix” (quoted because I invented this term). Let’s call this matrix M, M takes an input of one object space’s coordinates and outputs the same position in another object space’s coordinates like this:

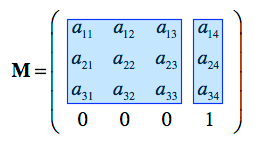

Specifically, the first 3x3 entries applies the transformation of scale and rotation, and the last column applies the translational (translation is the terminology for position) transformation. For more detailed breakdown and how to extract individual scale, rotation, translation matrices, please give this post a look which is very well written.

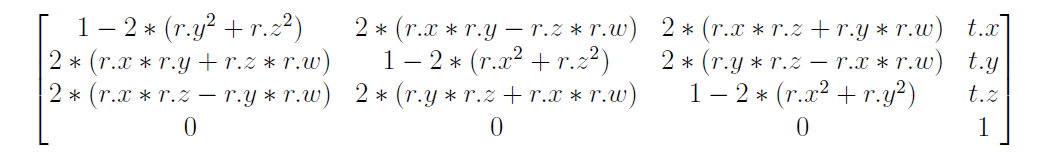

How do we calculate M? The answer is dependent on the two spaces we are transforming from and to. We just need to define the required scale (S), rotational(R), and translational(T) changes/matrices of from -> to and then M = S * R * T (or T * R * S depending on the context). However, here is a very common M we should know and I will use it to demonstrate the magic of space transformation matrix. This common matrix is the transformation matrix from an arbitrary object’s space to world space. Given the object’s scale s, rotation r (a quaternion, if you are not familiar with quaternions, just treat them as an 1x4 vector of numbers), and translation t in world space, M is:

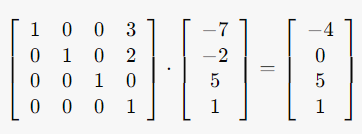

This looks intimidating, but since I am only demonstrating the cubes and they are not rotated or scaled, the entire upper-left 3x3 sub-matrix is just an identity matrix. For example, let’s say I want to calculate Cube B’s coordinate in world space, given Cube B’s coordinate in Cube A’s space and the transformation matrix M (plugging in Cube A’s scale <1, 1, 1>, rotation <0, 0, 0, 0>, and translation <3, 2, 0> in world space to the big formula above) from Cube A’s space to world space, the result is:

Where (-4, 0, 5) is indeed Cube B’s coordinate in world space! We have now seen how “space transformation matrix” can help us transform the coordinates in one space to another space. If rotation and scale are added, this method still works. The resulting coordinate is likely going to contain decimals which are hard to plot initially in the Space section and that’s why I did not rotate the cubes.

Finally Back to Cameras…

Sorry for the long detour! But we finally possess the necessary prerequisites for understanding cameras (and you will realize how stupid it is to have so many terminologies like view matrix/camera extrinsic/camera intrinsic/whatever instead of just the space transformation matrix from X’s space to Y’s space).

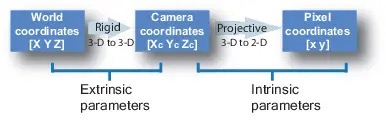

So, what a camera essentially does is that it transforms a 3D object to a 2D image, meaning transforms a bunch of 3D coordinates to 2D coordinates. It receives an object’s coordinates in world space initially and transforms them in 2 phases:

- Phase 1: Transform coordinates in world space to coordinates in camera space. Like every space transformation, this is done by a space transformation matrix M called view matrix or camera extrinsic, or, I just call it the space transformation matrix from world space to camera space. If you think about it, you already know how to calculate M based on previous reading:

- Camera is no different than a cube or an object, so you can easily get the space transformation matrix M’ from camera space to world space given camera’s scale, rotation, and translation in world space. Just plug in those to the giant formula above.

- M’ transforms coordinates from camera space to world space, M transforms coordinates from world space to camera space. Let’s say we initially have a translation vector X in camera space, this means M * M’ * X = X (basically it means that after transforming X from camera space to world space, we should be able to get the same X in camera space after transforming from world space back to camera space), which means M * M’ = I ==> M and M’ are inverse of each other ==> M = inv(M’).

- Phase 2: Transform coordinates in camera space to coordinates in pixel space involving a dimensionality reduction. This space transformation matrix is called camera intrinsic. I am not an expert on this matrix, but it has a focal length and works like the pinhole camera in middle school Physics. For more information, this page offers a great introduction!

And that’s it! That’s entirely how a camera works! Hopefully this post is helpful to your understanding of cameras. I am so disappointed that I have seen no clear and thorough tutorial on such a simple subject :( By the way, please note that there are other types of cameras than pinhole cameras, and they may have a different Phase 2 (very rarely, even a different Phase 1).

Novel View Synthesis and Unity’s cameraToWorldMatrix and worldToCameraMatrix, Lessons Learned

(This part of the blog is not intended for educational purposes, it explains why do I even bother learning about cameras and serves as a note to my research lab members, but feel free to read it just for fun(?))

So, I have been researching in the field of volumetric videos and novel view synthesis for some time. Specifically, I am currently trying to reproduce InstantAvatar’s novel views by moving the camera whereas InstantAvatar doesn’t move the camera but rather moves the SMPL model. To this end, I simulated a circular (around y-axis, x and z set to 0) motion of camera in Unity and recorded the trace of Unity’s cameraToWorldMatrix (InstantAvatar actually accepts a parameter of c2w, which is set to np.eye() in its original repository) so that I hope to do novel view synthesis from every angle. However, I got all blank results. After numerous rounds of experiments, I finally identified one issue and hypothesized another, both requiring me to actually understand “camera matrices”:

- Issue 1: The SMPL model of InstantAvatar is not at the origin, every dataset’s model has a different initial offset so that camera at origin can see it from a distance (otherwise if SMPL model is at origin, it overlaps with camera and we can see nothing) apart. Actually, to solve this issue, I could simply make Unity’s camera move around (offset_x, 0, offset_z), but strangely I didn’t come up with this simple fix on top of my head immediately. Instead, I decided to move the camera by modifying its c2w matrix. I am glad that I chose the harder path because without it, I might not even realize Issue 2. The fix is fairly simple, just add offset_x to

c2w[0, 3]and add offset_z toc2w[2, 3]so that camera doesn’t look at origin but SMPL model. - (Possible and later confirmed) Issue 2: After fixing Issue 1, I started to see some images from various angles, but most images were still blank, which shows my approach is somehow on the right direction. I noticed this line from Unity’s documentation of cameraToWorldMatrix: “Note that camera space matches OpenGL convention: camera’s forward is the negative Z axis. This is different from Unity’s convention, where forward is the positive Z axis”. I felt this is problematic because InstantAvatar’s SMPL visualizer treats forward as the positive z-axis. Therefore, I decided to treat camera the same as a cube and build the “native” object space -> world space transformation matrix manually using the huge formula above. After this fix, I was able to generate all views perfectly! Later I also found out that Unity has a built-in API to calculate space transformation matrices. The difference between

Matrix4x4.TRS()andCamera.main.cameraToWorldMatrixis just that the 3rd column in the formula above is negated, which means only s.z is negated.

![]()

So, I guess the most important lesson is that if we want to collect traces in Unity (which most likely we will since Unity can directly access headsets’ data like Oculus), we need to make sure all spaces (world, camera, pixel (if applicable)) align between Unity and the repository we are using for novel view synthesis.

Calculate Quaternion From TRS Matrix

(Again, you don’t need to know this part to get a rough idea of cameras, just a note for myself and lab mates)

Later, I needed to synchronize the rotation in recorded trace (lol). But the problem is that I only recorded TRS matrix and not direct rotation such as quaternions or euler angles. Obviously one could simply also record the rotation, but why bother doing so when we can directly calculate the quaternion represented by a TRS matrix?

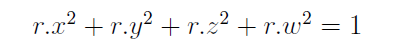

Prerequisite: all quaternions (accessed/stored/computed) in Unity are unit quaternions, meaning:

If a quaternion is not unit, it does not represent a rotation (Unity normalizes all quaternions behind the scenes). The reason I didn’t mention this before is that it would make previous sections too complex. Now, let’s further assume scale s = <1, 1, 1> because it would make the math look much nicer (I’ll talk about how to calculate quaternion when there is an actual scale later), which changes the TRS matrix to:

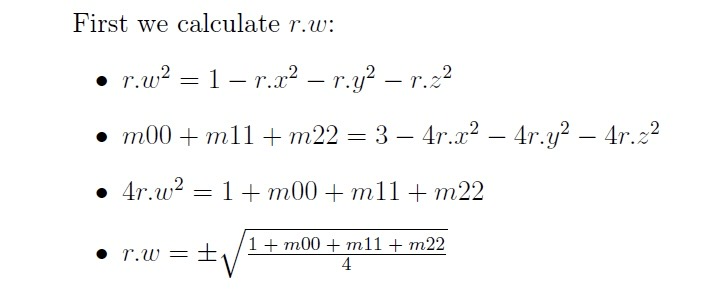

We can finally calculate quaternion r = <r.x, r.y, r.z, r.w>. We will start with r.w. I am going to do the math in LaTeX:

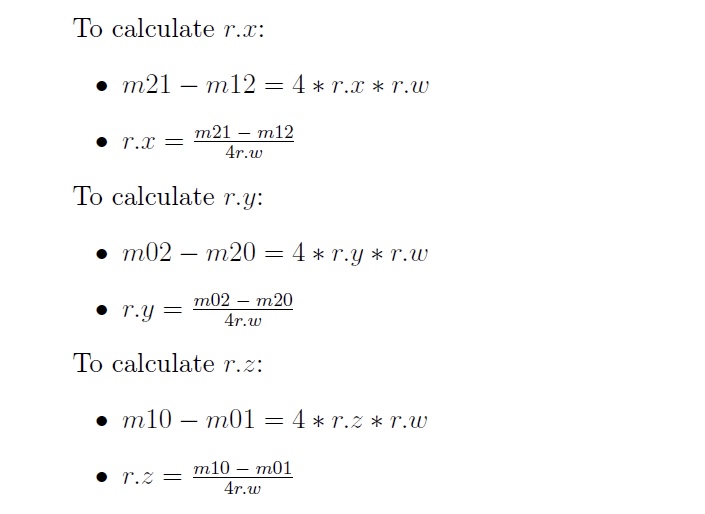

Theoretically, we can solely rely on the main diagonal to calculate r.x, r.y, and r.z, but that involves 3 square roots, which is (1) slow and (2) inaccurate due to floating point numbers. Since we already have r.w, we can simply calculate the rest one by one:

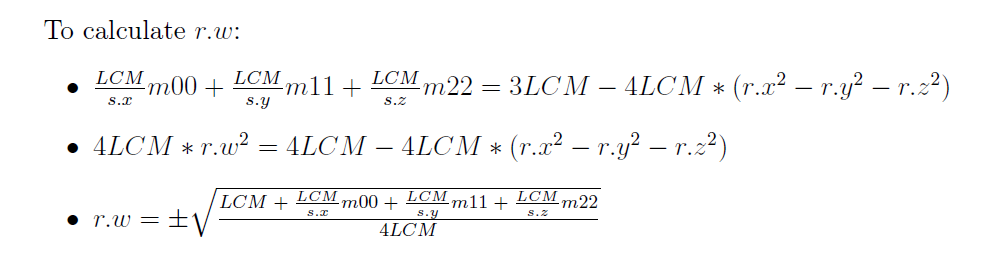

And that’s how we calculate the quaternion from the TRS matrix! Now, when there is an actual scale s = <s.x, s.y, s.z>, the technique is to find the least common multiple LCM of s.x, s.y, and s.z. Then:

Similarly, we can find the least common multiples of s.x and s.y, s.x and s.z, s.y and s.z to calculate the rest. I am not going to do the math because it is really tedious.